|

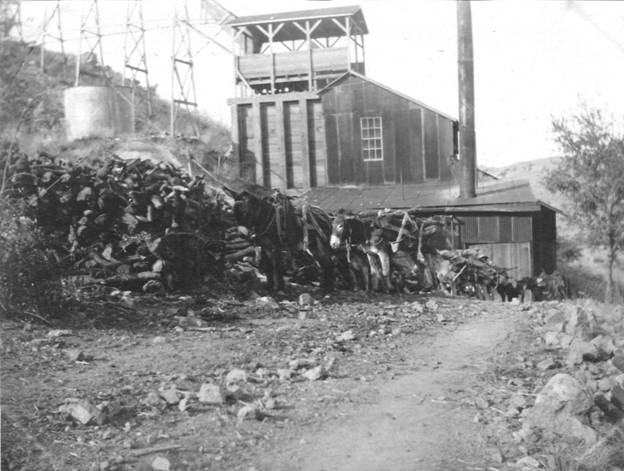

Photo of Oro Blanco mill |

Column No. 2

Bob Ring, Al Ring, Tallia Pfrimmer Cahoon

Let’s begin our trip along the Ruby Road with a little mining history and the

story of the first American gold mine in the Oro Blanco area. We’re talking

about a place a few miles south of Arivaca, just north of the Mexican border.

Except for Spanish Conquistadors, who roamed the southwest in the 1500’s looking

for seven cities of gold, Europeans first came to the Santa Cruz Valley in 1691

in the person of Jesuit priest Eusebio Kino. Over the next few years, as a part

of Spanish missionary expansion from Mexico, Father Kino established missions

along the Santa Cruz River at Tumacácori, Guevavi, and San Xavier.

Local mining history began in 1736, when prospectors made a fantastic silver

strike at Arizonac, just southwest of present day Nogales. This discovery

attracted thousands of European fortune seekers, some of whom drifted northward,

along the Santa Cruz River.

A few of these unsuccessful miners from the south, and a few missionaries

looking to add to their meager income, were the first people to explore mining

in the Oro Blanco area, probably around 1740. And they named the region Oro

Blanco (white gold), because the gold they found in streambeds had a high silver

content, giving the ore a whitish color.

The Oro Blanco area became Mexico’s responsibility, when Mexico gained its

independence from Spain in 1821. Finally, Oro Blanco became United States

property, with the Gadsden Purchase in 1853.

American mining in Oro Blanco started soon after, but constant Apache raids and

the absence of the protective military during the Civil War, made the area a

very dangerous place to live and work. After the Civil War, with the return of

the military, mining in Oro Blanco resumed in relative safety.

Just in time for serious mining in the south-central Arizona Territory, the U.

S. Congress passed the Mining Law of 1872. This law provided for mining

districts and set official guidelines for “locating” and recording mining

claims. For example, the law limited the size of each mining claim to 1,500 feet

by 600 feet.

Legally, “locating” a mining claim was fairly easy. The location required

official recording of the name of the mine, location date, name of locator,

size, boundary markings, and home mining district.

But locating a mine established mineral rights only. If the mine owner didn’t

perform at least $100 worth of labor and/or improvements on the mine each year,

the location lapsed, and others could locate the same “hole in the ground.”

(This is why mining claims changed hands so much.)

To get title to the land itself, the mine owner had to “patent” the mine, a

process that took up to a year and cost the miner some money. Not surprisingly

patenting occurred only when the mine owner had convincingly proven value of the

mining claim. (And this is why mines owners patented so few mines.)

A man from Tucson, Robert Leatherwood, located the Oro Blanco area’s first

American gold mine on March 20, 1873. Leatherwood fittingly named the mine, the

Oro Blanco. He found evidence that the Spanish worked his gold mine as early as

the 1700’s. There were large oak trees growing in old trenches dug in the

ground.

At the time, Leatherwood wasn’t sure that his mine was actually in Arizona. So

he surveyed the mine site and determined that his mine was indeed in U. S.

Territory, in fact just two and half miles north of the border. (Along today’s

Forest Road 217, about three miles south of Ruby)

Robert Leatherwood became a well known Arizona pioneer and colorful character.

He was only five feet five inches in height and weighed a scant 130 pounds. He

compensated for his small stature with a feisty attitude, often demonstrated

fearlessness, and a readiness to fight if required.

Leatherwood was born in North Carolina in 1844. He was a scout for the

Confederate army and proudly wore the Confederate uniform at important functions

all his life. He was even buried in it.

Leatherwood came to Tucson in 1869 and started out in the livery stable

business. While operating the Oro Blanco mine (and 14 other local gold mines),

Leatherwood also began a long political career in Tucson. He served as mayor of

Tucson in 1880, was a three-term representative to the Arizona Territorial

Legislature, and was Sheriff of Pima County from 1894 to 1898.

According to local legend, while Leatherwood was mayor of Tucson in 1880, right

after the completion of the southern route of the transcontinental railroad in

Tucson, he sent off telegrams to a large number of U. S. dignitaries, including

President Hayes, and to the Pope in Rome, announcing the completion of the

railroad and inviting them to the celebration in Tucson. At a big banquet to

celebrate the new railroad, the emcee read the supposed reply from the Pope

(printed in Arizoniana, 1960, by Mable Forseth Below):

His Holiness the Pope acknowledges with appreciation receipt of your telegram

informing him that the ancient city of Tucson has at last been connected to the

outside world and sends his benediction, but for his own satisfaction would ask,

where the hell is Tucson?

The original Oro Blanco gold mine was to enjoy a long, if only intermittently

successful, history. But that’s another story. (Hint: The Oro Blanco gold mine

was never patented.)

(Sources: James Brand Tenney, History of Mining in Arizona; Tucson Citizen;

Arizona Daily Star; 1872 Congressional Mining Law, Arizoniana, Arizona

Historical Society Clip Books)

|

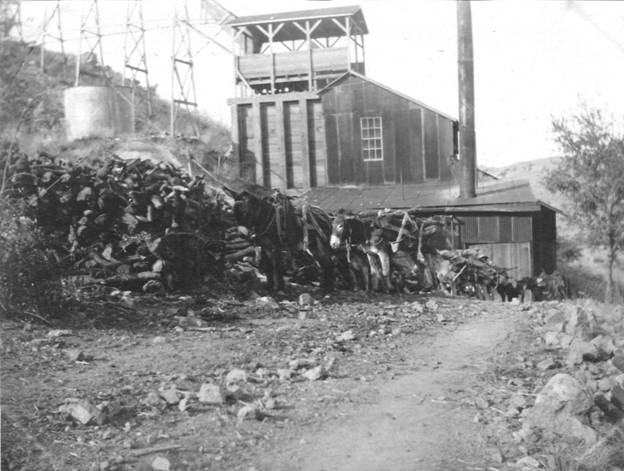

Photo of Oro Blanco mill |

NEXT TIME: ALONG THE RUBY ROAD The Birth of the Oro Blanco Mining District