|

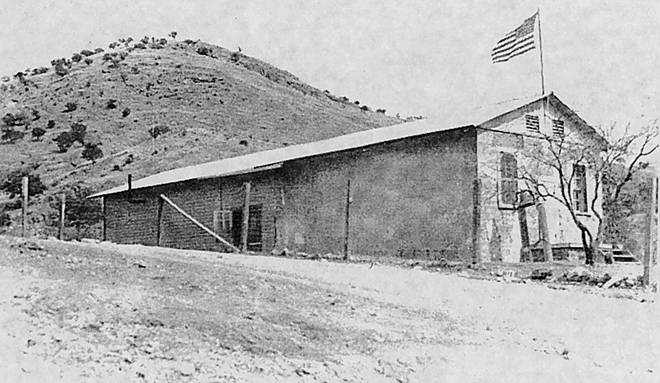

Ruby school

|

|

|

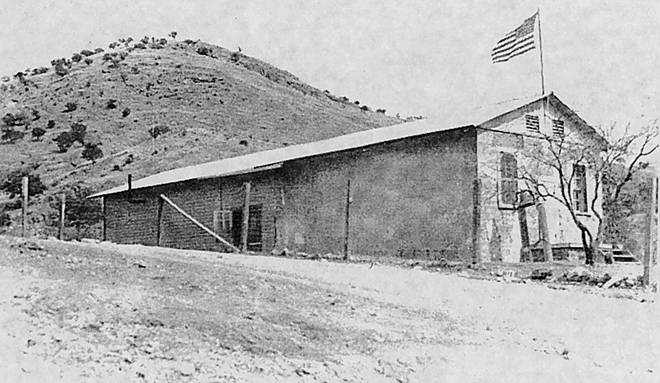

Montana Dam

|

Column No. 12

Bob Ring, Al Ring, Tallia Pfrimmer Cahoon

In 1917 and 1918, Ruby’s Montana mine successfully, although painfully,

transitioned from producing silver and gold to producing mostly lead and zinc.

Meanwhile the other mines in the Oro Blanco Mining District, mostly gold mines,

really struggled.

There was an increasing market for lead and zinc. Bullets and paint contained

lead, and rust-resistant galvanized iron and calcimine coatings used zinc.

Increased use of these products and U. S. preparations for World War I drove up

prices and made large-scale mining of lead and zinc more cost effective.

Merchandizing leader Louis Zeckendorf, owner of the Montana mine since the late

1880s, had been trying to sell the mine for years. When lead and zinc mining

became more attractive, he hired Tucson lawyer Francis Henry Hereford to be his

selling agent. Zeckendorf made Hereford’s job harder by constantly raising the

asking price. With one eye on the increasing price of zinc, over a period of

only a few months, Zeckendorf raised his price for the Montana from $100,000 to

$125,000 to $150,000 to $160,000.

Finally on February 17, 1917, Hereford negotiated a lease agreement with an

option to buy the mine for $140,000 with the Goldfield Consolidated Mining

Company (GCMC).

George Wingfield ran the GCMC. According to the Nevada State Journal, Wingfield

was “the most powerful financial and political figure in Nevada during the first

half of the 20th century.” Wingfield’s mining activity started in the early days

of the Tonopah Nevada gold boom in 1903, when as a banker, he helped finance the

fabulously rich mining area that became known as Goldfield.

The GCMC formed a subsidiary, the Montana Mines Company, to work the Montana

mine. The Company’s first job was to pump water out of some of the long-inactive

tunnels and remove the muck that had accumulated over several years of limited

activity. Since lead and zinc were deeper underground than the gold and silver

mined previously, the company worked hard to extend the main shaft to 200 feet

depth. They built a heavy-duty concentration mill with a capacity for handling

150 tons of ore daily. The Company also constructed a large storehouse, a

bunkhouse, a staff office, and an assay office.

Mining operations started off at a good pace.

Five immense 5 ½-ton Mack trucks, with chain-drive rear wheels and solid tires,

hauled ore concentrates from the mine to the distant railroad that ran

north-south along the Santa Cruz River. At first the Company shipped the ore

concentrates over the longer road to Arivaca and on to a station at Amado. But,

by early September 1917, workers completed improvements on the shorter road over

the Atascosa Mountains to newly built Plomo station at the Pesqueira Bridge, a

few miles north of Nogales.

The trucks operated 24 hours a day. On the return trip to the mine, the trucks

hauled oil and other supplies.

The Montana Mines Company shipped an average of four boxcars weekly of lead and

zinc concentrate to smelters in Texas.

By October 1917, there were 100 men “employed in the mine and mill, both night

and day.”

During this active time, there was usually work for everyone. Residents of that

period built most of the adobe buildings that stand today in ruins. They

finished the schoolhouse on October 1, 1917. A boarding house helped accommodate

the mining family and visitors. And a new general store built in 1915 (see our

next column), served both Ruby and the surrounding area.

At the same time, the Montana Mines Company built a new telephone line to

connect Ruby to Nogales. Engineers installed a telephone in the Ruby general

store. A six-times-a-week mail service by automobile now operated between

Nogales and the Ruby Post Office (in the same general store).

But operations didn’t go as planned for long at the Montana mine. Throughout the

fall and early winter of 1917, problems plagued the mine: the milling operation

was not working properly, there were equipment problems, and problems with the

new freighting trucks.

Severe rains in early September made the road to Amado impassable. After they

started using the improved shorter road over the mountains, they found that the

round the clock operations of the monstrous trucks started wearing away the

road, especially the mountain curves. They had to assign a dedicated crew to

keep the road repaired.

In early October, the Montana Mines Company completed a new dam to store water

to power the steam engines in the mill, but “as luck would have it,” there was

no rain for weeks after the dam was completed.

In an internal GCMC memo, dated January 7, 1918, a company executive,

summarizing GCMC’s generally positive overall western state operations, says of

the Montana mine: “I might state that the Montana mine which we have been

working on in Arizona for the Goldfield Consolidated is a failure.”

So what had begun so promisingly only a year earlier, ended badly. On February

23, 1918, the GCMC announced the suspension of operations at the Montana mine.

According to Arizona Bureau of Mines records, during the Montana Mines Company

operation, the Montana mine produced 1,250,000 pounds of lead, 1,300,000 pounds

of zinc, and a small amount of silver and gold. The value of the lead and zinc

ore produced was $202,000.

This level of production, over eight months during World War I, might be

regarded as a success. But the Montana Mines Company spent $300,000 developing

the mine before producing the first concentrates, and by February 1918, had paid

$75,000 in option payments to Louis Zeckendorf (who retained ownership of the

Montana mine). So, measured against expenses, the GCMC operation of the Montana

mine was not a profitable operation.

It was however, an important step towards lead and zinc mining, for which Ruby

would be known in the 1930s.

(Sources: Francis Henry Hereford files, Arizona Historical Society; Nogales

Oasis; Nogales Border Vidette; George Wingfield Collection, Nevada Historical

Society; D. E. Andrus, U. S. Bureau of Mines Circular 6497, 1931; George M.

Fowler, AIM&ME paper, “Montana Mine, Ruby,” 1938)

|

Ruby school

|

|

|

Montana Dam

|

NEXT TIME: ALONG THE RUBY ROAD Phil Clarke and the Ruby Mercantile