|

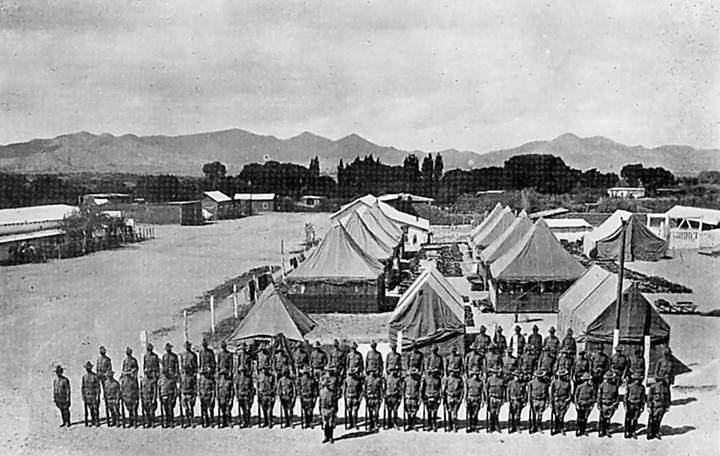

Troops in Arivaca camp From 1916 to 1919, U.S. Cavalry troops patrolled Arizona’s south-central borderland from this camp in Arivaca. (Photo courtesy of Origin and Fortunes of Troop B: The Connecticut National Guard, by James L. Howard, 1921) |

Column No. 14

Bob Ring, Al Ring, Tallia Pfrimmer Cahoon

The 1910s and 1920s were a particularly dangerous time along the border between

Arizona and Mexico.

Just after Phil Clarke bought the Ruby general store in 1913, “unknown parties”

shot and killed another storekeeper, Jasper S. Scrivener, owner of the store at

Oro Blanco camp (old Oro Blanco) just three miles away. The Tucson Daily Citizen

reported Scrivener’s murder:

As the scene of the crime is only two miles from the Mexican border, it is quite

probable that the murderer has crossed. Scrivener was in his store at the time

and the shooting was done through the window. He is said to have had $1,400 in

gold dust on the premises.

Ever wary of bandits from nearby Mexico, Phil Clarke kept loaded guns in every

nook and cranny of his Ruby store.

In later years Clarke told this humorous story about a Mexican customer,

illustrating the lengths that Clarke would go to protect his family and store:

As he was leaving he spotted a rain gauge that I had recently put up. It was an

old-fashioned large style apparatus that stood on a big pipe. He wanted to know

what on earth it was. I told him it was a new weapon that held poison gas. All I

had to do was press a button in my bedroom and it would release a big spray of

gas, enough to kill a whole regiment of soldiers! He was very impressed and

carefully rode way around it as he left.

Whether or not this fanciful story had anything to do with it, as Clarke said

later:

I never did have trouble to speak of with the Mexicans because they were friends

of mine. The bad element amongst them knew that I was a good shot. I was once

Golden Gloves bantamweight champion of the U.S. and they had seen my fists on

occasion and respected my ability.

Cattle-rustling was also a problem along the border. Referring to the area south

of Arivaca, the editor of the Nogales Oasis wrote in 1915:

. . conditions with the cattlemen out in that part of the country are very

unsatisfactory. Petty depredations from the Mexican side of the line are

frequent and almost continuous and the loss of cattle is heavy . . estimates

that within a few months, between Sasabe and Nogales at least 1,000 head of

cattle have been run across the line and slaughtered.

Mexican revolutionists also plagued the border between the United States and

Mexico from Texas to California. From 1910 to the late 1920s, Mexico suffered a

number of violent revolutions. There were many incidents of murder, robbery,

kidnapping for ransom, property destruction, and even an invasion of U.S.

Territory by “Pancho” Villa, who raided Columbus, New Mexico in March 1916.

The U.S. response to Villa’s raid was to send a punitive expedition under

General John J. Pershing into Mexico. (For almost a year, Pershing’s troops kept

Villa on the run, but they never captured him.)

A second U.S. response to Villa’s Columbus, New Mexico raid was the mobilization

of the National Guard. On June 18, 1916, U. S. President Woodrow Wilson “called

out the militia from every state in the country for service on the Mexican

border.”

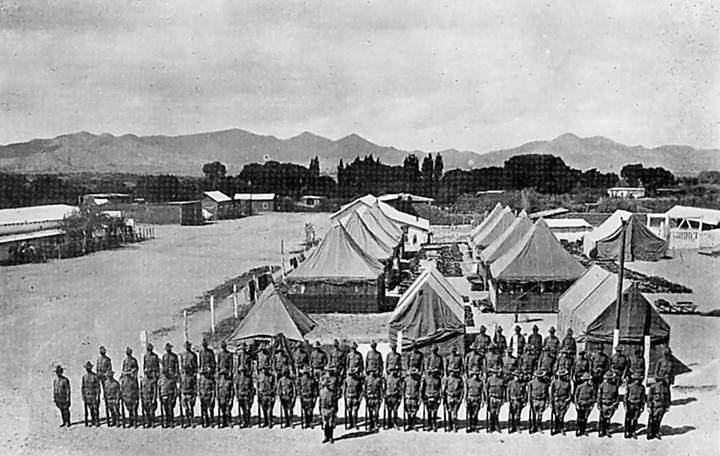

The U.S. established new military camps in remote areas, including one at

Arivaca, just north of Ruby. The first troops in Arivaca were Connecticut

National Guardsmen, who arrived in August of 1916. The Utah Cavalry replaced the

Connecticut National Guard in late 1916.

On January 26, 1917, a border incident occurred at Casa Piedra (Stone House),

just three miles south of Ruby and 16 miles south of the new military camp at

Arivaca. According to the next day’s Tucson’s Arizona Daily Star:

The trouble started yesterday morning when six American cowboys rode to the line

to drive back some American cattle which are reported to have been close to the

line, but on the American side. When they started to drive the cattle away they

were fired on by a force of twenty Mexican cavalry.

The cowboys reportedly withdrew northward until 14 U.S. cavalrymen from Troop E,

Utah Cavalry, from Arivaca reinforced them. Later that day, an additional 18

troopers from the Arivaca camp arrived to increase the American force. The

troopers left a few of the men at Ruby to guard the Montana mine. (This was the

time when the Goldfield Consolidated Mining Company was busy developing the

mining property.) The Americans and Mexicans exchanged fire for the rest of the

day, with no American casualties. By the next morning, the Mexicans had departed

and the so-called “Battle of Ruby” was over.

This was not a major international incident, but in the Oro Blanco Mining

District, “hard feelings between Americans and Mexicans were intensified by this

episode.”

In February 1917, after a negotiated settlement with Mexico, the 10th U.S.

Calvary returned to the U.S. with General Pershing from Mexico and replaced the

Utah Cavalry in Arivaca. The 10th Calvary, made up of African American troopers,

began to patrol south-central Arizona on a regular basis. (The 10th Cavalry’s

squadron camp was at Camp Stephen D. Little in Nogales, but detachment squadrons

occupied camps at Arivaca and the village of Oro Blanco. Soldiers also manned a

troop outpost in Bear Valley, a few miles east of Ruby.)

The Yaqui Indians also contributed to border turbulence near Ruby. The Yaqui

used a border-crossing trail through Bear Valley to smuggle arms and ammunition

to their tribesmen in Mexico who had for some time been in revolt against the

Mexican government. The Yaquis would sneak across the border, work in U.S. mines

and on ranches to accumulate money, then purchase rifles and ammo and return to

their people in the Yaqui River section of Sonora.

On January 9, 1918, a group of about 30 Yaquis, traveling on foot through Bear

Valley, ran into a group of 10th Cavalry troopers. The Yaquis apparently mistook

the black soldiers of the 10th Cavalry for Mexican soldiers and opened fire.

Following a short fight, U.S. troopers captured 10 Yaquis. There were no

American casualties.

National Guard troops, first deployed to Arivaca in August 1916, remained there

only three years. By late 1919 the troops in Arivaca had departed, leaving the

border area near Ruby unprotected.

This would have grave consequences for Ruby just a few months later.

(Sources: Tucson Daily Citizen; Nogales Oasis; Phil Clarke “Recollections of

Life in Arivaca and Ruby, 1906-1926,” Arizona Historical Society; Nogales

Herald; U. S. Army Center for Border History; Mary Noon Kasulaitis, “National

Guard Operations in Arivaca, Connection, 1998; Arizona Daily Star; Carol Clarke

Meyer, “The Rise and Fall of Ruby,” The Journal of Arizona History, 1974; Major

Albert G. Scooler, “Cavalry’s Last Indian Fight,” Armor, 1970)

|

Troops in Arivaca camp From 1916 to 1919, U.S. Cavalry troops patrolled Arizona’s south-central borderland from this camp in Arivaca. (Photo courtesy of Origin and Fortunes of Troop B: The Connecticut National Guard, by James L. Howard, 1921) |

Next time: The Fraser Brothers Mining Story