Column No. 21

ALONG THE RUBY ROAD

The Pearson Murderers Escape

Bob Ring, Al Ring, Tallia Pfrimmer Cahoon

Following their trials and convictions for the murder of Frank Pearson at the

Ruby mercantile on August 26, 1921, Placido Silvas and Manuel Martinez were to

be transported to Florence prison so that Martinez could be hanged and Silvas

could begin serving his life sentence.

At 5:00 pm on July 13, 1922, Santa Cruz County Sheriff George J. White and

Deputy Leonard A. Smith left Nogales by automobile with the prisoners. The

Sheriff had tire trouble in Tubac and had to call Nogales for another car to be

sent to them. In the substitute car, with Sheriff White driving, they resumed

the trip at high speed, apparently trying to make up the time they had lost in

Tubac.

As Deputy Smith told it later, about 18 miles south of Tucson, a mile north of

the town of Continental, “the car traveling at a high rate of speed estimated

later at 35 mph, struck a sand wash. Swerving from side to side of the road . .

the car finally completely left control of the sheriff and was overturned in a

deep ditch bordering the highway.”

Sheriff White died instantly in the wreck and Deputy Smith, in the front seat

with White, sustained serious injuries. Silvas and Martinez, who had been riding

in the rear seat handcuffed together, survived the crash with no serious

injuries and escaped into the Arizona desert.

Southern Arizona’s law enforcement community responded immediately. By the next

day, Pima County Sheriff Ben Daniels and Cochise County Sheriff Hood headed

posses in the field. (Santa Cruz County was slower to react because of the death

of Santa Cruz County Sheriff White.)

Arizona’s Governor Campbell ordered the Superintendent of the State Penitentiary

in Florence, Thomas Rynning, to join the search. Post Office Inspector E. D.

Chance (connected to the crime in Ruby because of the theft of U.S. mail) joined

the manhunt. Authorities also added an Indian tracker to the posse.

Soldiers from Camp Stephen D. Little in Nogales deployed to Arivaca to broaden

the law enforcement net and search an area where both escapees had once lived.

Other troops from Nogales, the 17th Infantry and a motorcycle corps, rushed to

the border to guard the international line.

There were all sorts of wild theories about where the escaped murderers were

headed. One theory, quickly discounted, was that a trailing automobile

(accomplices) “rescued” the prisoners and quickly crossed the border into

Mexico.

Some believed that Sheriff White had been struck by one of the prisoners with a

tool, causing the wreck, but Deputy Smith stated “that no blow had been struck”

and that the prisoners did not cause the accident.

Another theory had the escapees heading towards the eastern part of Santa Cruz

County, looking to cross the border south of Patagonia. Literally every man in

the Patagonia district mobilized for a search that found no trace of the

fugitives.

Trackers found footprints near the crash site and followed them towards the

south. The footprints indicated that Silvas and Martinez were probably still

handcuffed together, the prints being only a few feet apart. Billy Chester, a

noted animal hunter, brought two bloodhounds to the chase. As time went on, and

the murderers remained at large, more and more men went to strategic border

crossings to the south, hoping to intercept Silvas and Martinez.

On July 16, on the third day following the escape, newly appointed Santa Cruz

County Sheriff, Harry Saxon, formed a posse from Nogales. By now the posses

numbered over 200 men, one of the largest manhunts in Arizona history. A vast,

encircling human net tightened on Silvas and Martinez.

On July 17th, Deputy Smith died from the injuries he suffered in the car

accident.

The death of Sheriff White, and then Deputy Smith, spurred the posses and

angered the residents of southern Arizona. Feelings ran high against the escaped

murderers.

Finally, on July 18th, shortly before noon, the posse headed by Sheriff Saxon

found Silvas and Martinez weak and exhausted, hiding among the rocks, about two

and half miles southwest of Amado. They had managed to travel only about 15

miles from the crash site in a southwesterly direction, with the safe haven of

the international border still more than 20 miles distant. When the posse found

them, they were not handcuffed together, but were still wearing the handcuff

bracelets.

Law officers immediately returned the prisoners to Nogales where an angry, but

not unruly, crowd of 1,000 people awaited them.

A representative of the Nogales Herald interviewed Silvas and Martinez in the

Nogales jail. The prisoners related how they had early on broken the handcuffs

chain with a rock. Neither ate for four days, subsisting on water that they

found in arroyos and maguey, a desert plant. They traveled by night, and hid

during the daylight hours. Silvas said that they stayed together because he knew

the country and Martinez didn’t. Even so, Silvas said that they started off in

wrong direction and had to turn back. (Silvas wanted to head towards his home in

Arivaca.) On the third day after the automobile accident, they saw one of the

posses looking for them.

On July 20, 1922, one week after the prisoners’ escape, Sheriff Saxon and two

deputies delivered the handcuffed and shackled Martinez and Silvas to Florence

prison by automobile without incident.

(Sources: Tucson Citizen, Nogales Herald)

|

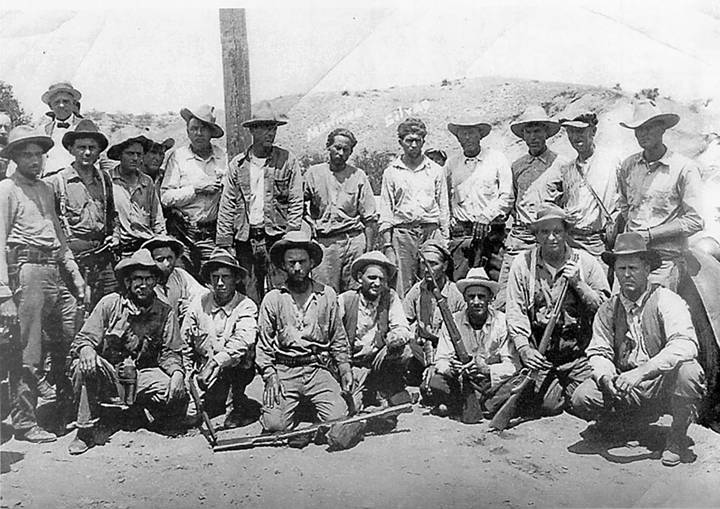

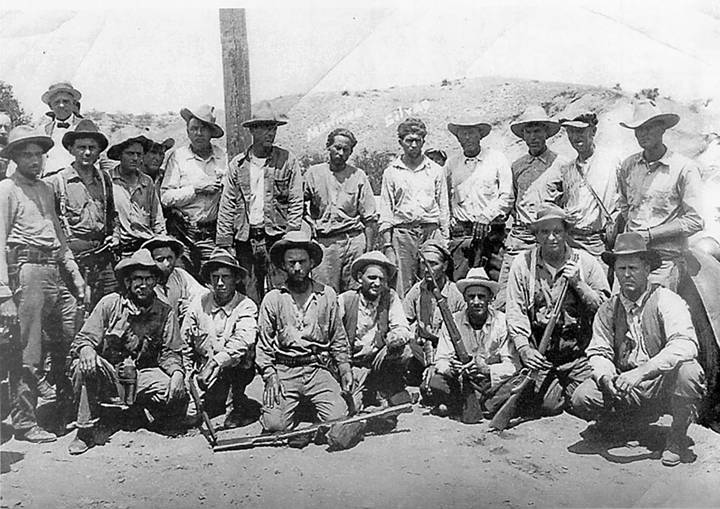

Posse and prisoners

Over 200 men pursued the Pearson’s murderers after they escaped during

transport to the prison in Florence. Silvas and Martinez are in the background

in this photo taken with some of the posse immediately after capturing the

fugitives. (Photo courtesy Nogales Herald, July 20, 1922) |

Next time: The Pearson Murderers Fate

Back to List of Columns