Column No. 25

ALONG THE RUBY ROAD

Ruby’s Montana Mine Becomes the Largest Producer of Lead and Zinc in Arizona

Bob Ring, Al Ring, Tallia Pfrimmer Cahoon

Following four years of shutdown during the Great Depression, the Montana mine

restarted production in April 1934. Thirty men went to work right away to repair

the mill and retimber the mine. The Eagle-Picher Lead Company assigned E. D.

(Ed) Morton to be the general manager of the renewed operation. Walter Pfrimmer

(columnist Tallia Pfrimmer Cahoon’s father) was Chief Engineer.

Eagle-Picher’s development work during the years that production had been closed

down, now paid off. The mining operation grew rapidly. By mid May, there were 98

men on the mine’s payroll.

The Montana now had a vertical shaft 750 feet in depth with six principle

working levels at 100, 200, 300, 400, 525, and 660 feet from the surface. There

were three additional intermediate levels at depths of 75, 585, and 625 feet.

Lateral drifts extended up to 2,000 feet on some levels, with a total of over

10,000 feet of workings.

The Montana mill sat on a steeply sloping hillside. The mill’s primary structure

was galvanized iron and timber, with concrete foundations for the heavy

machines. The fully equipped mill had a steel head frame, electric hoist, and

all necessary accessories to carry on mining operations. The mill had a capacity

of 400 tons of ore per 24 hours. Eight Fairbanks-Morse Diesel engines, with an

aggregate capacity of 960 horsepower, generated power for mining and milling

The largely-automated milling process consisted of crushing and grinding the ore

to the size of sand and then adding chemicals to release the lead and zinc from

the constituent ore and produce concentrates of each metal.

The tailings (refuse or left over material) that resulted from the concentrating

process settled in a sump. From there a pump moved the material to one of two

tailings dams located 800 feet away. The solid material in the tailings

gradually settled out. Two men maintained the sides of the tailings dams during

the day shift. Always mindful of the shortage of water, Eagle-Picher reclaimed

75% of the water contained in the tailings pulps.

The milling process resulted in a 97% recovery rate for lead and 85% recovery

for zinc.

Silver, gold, and copper were important byproducts from the milling process. The

value of gold and silver obtained just about covered operating expenses.

After the milling operation crushed and processed the ore to produce lead and

zinc concentrates, diesel trucks hauled the concentrates to the Southern Pacific

Railroad in Amado.

On the return trip, the trucks carried timber for mining and general purposes,

support equipment, and oil. Suppliers shipped these materials to Amado by rail

from distant points to be brought back to the Montana mine.

Eagle-Picher shipped the processed ore to smelters in Texas. Lead concentrates

went to a smelter in El Paso and zinc concentrates to a smelter in Amarillo.

By September 1934, the Montana mine achieved a shipping rate of three railroad

cars of ore concentrates per week from Amado. But operations still grew rapidly,

and by early January 1935, the rate was a car and a half of ore concentrates

shipped daily, six days a week.

Three hundred men now worked at the mine.

Mining operations reached their peak in 1937. In May 1937, there were 350 men

employed by Eagle-Picher at the Montana mine. Ruby’s population topped off at

the same time at about 1,200 people.

The mine operated seven days a week with the men working three shifts per day.

In 1934, miners earned $2.50 per day; pay increased to $5.25 per day by 1940.

The mine shut down only on Christmas day and the Fourth of July for scheduled

maintenance.

The mining boom couldn’t last forever and it certainly didn’t. In mid 1939,

production started to slow, as the ore became harder to find. The number of men

working at the Montana mine started to decline.

By early 1940, the mining boom was over. The population of Ruby early that year

was 1,100, but quickly declined. Mining production continued, but on a

much-reduced scale.

Finally, in May 1940, Eagle-Picher suspended operations.

Unfortunately, there appear to be no surviving Eagle-Picher company records of

total production tonnage or value of the ore mined at the Montana.

However, we do have a value for the total tonnage of ore that Eagle-Picher

milled from the Montana mine between 1928 and 1940. The estimate, by geologist

Louis Harold Knight, in his detailed study of the Oro Blanco Mining District, is

773,197 tons, averaging 4.0 % lead, 3.9 % zinc, 5.4 oz/ton silver, and .06

oz/ton gold.

During the period from 1935 to 1939, the Montana mine became the largest

producer of lead and zinc in the state of Arizona.

The Arizona Bureau of Mines estimated the total value of the Montana mine’s lead

and zinc production from 1928-1940 at approximately $4.5 million.

After shutting down the mine, Eagle-Picher immediately dismantled the mill and

flotation system and reinstalled them in Sahuarita, about 60 miles to the

northeast, where they had another mining operation. Over the next four years,

the Company slowly dismantled the Ruby mining camp and removed all the buildings

except the adobe and concrete structures.

Ruby’s Post Office closed on May 31, 1941.

(Sources: Nogales International; Arizona Daily Star; The Connection; Mining

Journal; Western Postal Museum; discussions with former Ruby miner Leo Neal;

Louis Harold Knight, Structure and Mineralization of the Oro Blanco Mining

District, 1970; D. E. Andrus, “Milling Methods and Costs at the Montana Mine

Concentrator, U. S. Bureau of Mines Circular 6467, 1931; George M. Fowler,

“Geologic Report on the Montana Mine,” 1931; Frank J. Tuck, History of Mining in

Arizona, 1963; E. D. Wilson and G. M. Fowler, “Arizona Zinc and Lead Deposits,”

1951)

|

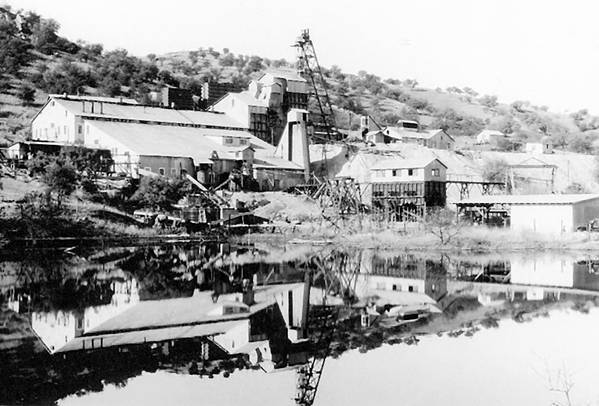

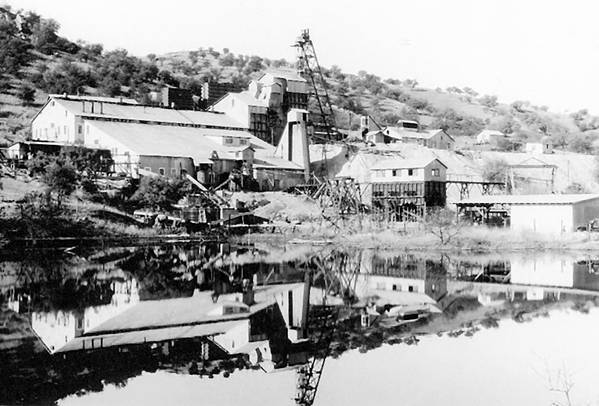

1934 mill By 1934, the Montana mine was ready to become

the largest producer of lead and zinc in Arizona. In this photo, the mill

buildings reflect in Ruby Lake (also called Town Lake), one of the

reservoirs that supplied water for the milling operation. (Tallia Pfrimmer Cahoon private collection) |

Next time: What it was like to live in Ruby