Column No. 27

ALONG THE RUBY ROAD

Working in the Montana Mine

“The hardest part was learning not to be afraid to enter the mine”

Bob Ring, Al Ring, Tallia Pfrimmer Cahoon

When Eagle-Picher took over the Montana mine in 1926, the Company immediately

rebuilt the mill to handle 250 tons of ore per day. In 1928, mining operations

purred along smoothly and so did the mining camp. But by 1929 the Great

Depression slowed mine operations and in 1930, the Montana mine shut down. The

Company laid off most employees. Mine operations did not start again until four

years later.

In 1934 the mine restarted production, with a newly modified mill able to handle

400 tons of ore per day. Eagle-Picher brought in Erle D. (Ed) Morton as overall

Ruby General Manager, responsible for the Montana mine, the mill, and the entire

mining camp. Morton held this position until the mine closed in 1940.

Grover J. Duff became the mine superintendent. He ran the day-to-day mining

operation. Columnist Tallia Pfrimmer Cahoon remembers that Duff was:

“Not very well liked by most but apparently, a good ‘task master’ because some

of the men who worked under him have told me that after leaving Ruby and looking

for another job, when they would say that they had worked for Grover Duff, they

had a job.”

Former miner Leo Leal recalled management’s tough side:

“Grover Duff, the superintendent, was very rough … the mine managers were very

strict, fired people every day. Ruby kingdom it was called … I was about 22 when

I started there. I never took ‘shit’ from anyone. They would holler at you, cuss

you and then fire you. … I was fired about 10 times, then after 10 days they

would hire me back.

But Leal also recalled management’s fairness: “Paid everybody equal, it was job

not race that determined pay rate.”

Eagle-Picher paid the miners twice a month ($2.50 per day in 1934, growing to

$5.25 per day by 1940). For those who wanted them, the Company issued coupon

books in $5 or $10 amounts. The Company deducted the value of the coupon books

from the miner’s paychecks. Coupons could be used around the Ruby mining camp

instead of cash.

The mine’s main shaft was now 750 feet deep with six principle working levels.

When a new man came to work in the mine, the Company gave him a hard hat and a

carbide lamp. If you worked at the deeper levels, you got boots for the water

that was often present.

A hoist, called the “cage,” took 8-10 men at a time down into the mine. Sheet

metal surrounded the cage up to about knee-level, with wire mesh above. A bell

system identified the shaft level as the hoist approached.

Huge timbers measuring 12-15 feet in length and about 10-12 inches square helped

strengthen the working tunnels on the various levels. The cage framework

extended well above the cage floor so the timbers could be stacked on end to be

lowered to one of the working levels. From there, the miners placed the beams on

flat cars that traveled on tracks in the tunnels. Miners set the beams

vertically every few feet. They supported horizontal timbers shoring up the

earth above.

Most of the Montana mine’s so-called miners were relatively inexperienced and

the tight tunnels at deep working levels could be intimidating. Many miners felt

that the hardest part was to learn not to be afraid to enter the mine.

At its peak, the mine operated seven days a week with over 300 men working

three, eight-hour shifts per day. As mill worker Charlie Foltz remembered:

“There was no time off for chow as a man could eat while working.”

Donn Bowman worked at the 300-foot level. Bowman told how miners did the

blasting, to break out the lead/zinc-rich ore, at the end of each shift. They

set dynamite cap fuses of varying lengths into holes drilled into the earth

about the size of a fifty-cent piece. After blasting, the next shift of miners

loaded the new broken earth into ore cars. These cars weighed about a ton each

and traveled on tracks that had been put into place by another crew. If chunks

of ore were too heavy to load into the car, they had to be broken up with

sledgehammers.

Bowman recalled what happened next:

“The car … was pushed along the tracks by each mucker to the shoot. Tramming

this was called. At the shoot, the cars were dumped. Pegs tabulated the number

of ore cars that had been emptied on a given shift.”

According to Bowman:

“Ventilation down in the mine was terrible. One would be down in a pocket for a

mere five minutes and be soaking wet.”

Arnucfo Yanez, who worked at the Montana mine for four years during the 1930s,

“got sick with mine-caused lung problems.” He later filed and won an Industrial

Compensation suit against the Eagle-Picher Company.

The Company constructed a large shower room, which included a changing room with

lockers, for the employees to use. According to Bowman:

“This very large, unclean room with several shower-heads had a depressed

concrete floor where the water drained. A chain with hooks was provided for the

men to hang their clothes.”

This facility allowed miners to clean up after their shift. This was

particularly convenient for those (including Bowman) who lived in the bunkhouses

where there were no showers.

Six big 350-horsepower diesel engines operated 24 hours a day and were very

noisy. The engines ran the mill flotation machinery, compressors that made

compressed air for underground jackhammers, and generators to make power for

electric lights and motors. These machines could be touchy and needed expert

care.

The master mechanic was a fellow named Hutchison, a tremendous man with a big

handlebar mustache. Mill superintendent Ed Crabtree recalled:

“Some place along the way, he had lost an eye, and had substituted a rather

imperfect one. Occasionally in the morning he would get this glass eye in

backwards and would go around all day with a white sphere glaring at you. It was

rather disconcerting. Some people wondered why the Company ever kept Hutch on

the payroll, because he was periodically drunk and would lay off the job for two

or three days. The real reason was that I doubt if anyone other than Hutchison

could have kept those … engines operating.”

(Sources: Interviews with Leo Leal, Charles Foltz, Donn Bowman, and James A.

Yanez; Edwin H. Crabtree Family History)

|

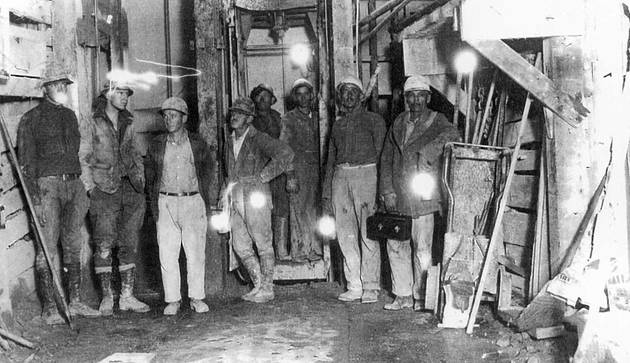

Miners Underground

Miners surround the underground elevator in the Montana mine. Mine manager

Frank Lerchen is fourth from left; mining engineer Walter Pfrimmer is

third from left. Circa 1928 (Tallia Pfrimmer Cahoon private collection) |

|

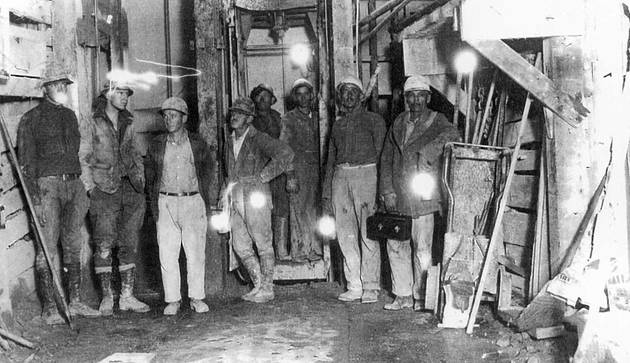

Timbers in Mine

Huge timbers shored up the working tunnels in the Montana mine. Circa 1928

(Tallia Pfrimmer Cahoon private collection) |

Next Time: Living Accommodations in Ruby

Back to List of Columns