|

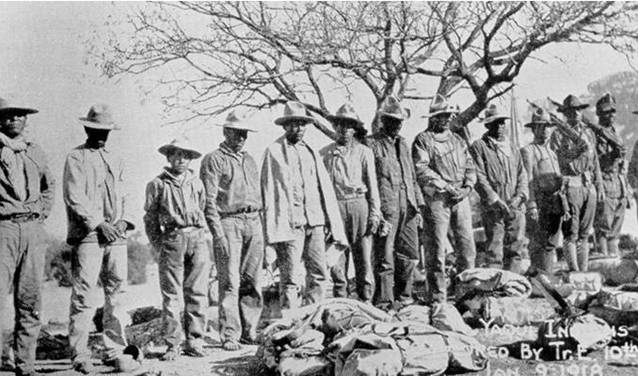

Captured Yaqui Indians Tenth cavalry troopers captured 10 Yaqui Indians after a short fight near Ruby in 1918. (Photo courtesy of Tenth Cavalry and Border Fights, 1964) |

Column No. 51

Bob Ring, Al Ring, Tallia Pfrimmer Cahoon

The first people in Oro Blanco country were Native Americans, probably the

Hohokam, a peaceful, agricultural people. The Hohokam lived in scattered

villages along rivers in the Sonoran Desert of central and southern Arizona

(including the Arivaca Valley, just north of Oro Blanco) for at least 1,500

years, until the 1400s, before mysteriously disappearing.

When Jesuit Father Eusebio Kino and the Spanish came north into present-day

southern Arizona in 1691 to start mission building along the Santa Cruz River,

they encountered Pima Indians, perhaps descended from the Hohokam, living in the

river valleys.

In 1751 the Pima, upset over having their best lands taken by the Spanish and

cruel treatment by Jesuit missionaries, revolted violently across northern

Sonora and southern Arizona. In one eruption, they attacked the small Spanish

settlement of Arivaca, just north of the Oro Blanco region, killing 13 people. A

few months later in 1752, the Spanish soundly defeated the Pima in a final

battle near Arivaca.

Sometime after A.D. 1200, the Apache entered the southwest from the north and by

the 1500s had spread into northern Mexico. The Apache were hunters, warriors,

and raiders, and were a problem from the beginning for Spanish prospectors and

settlers who drifted north into the Santa Cruz Valley from the Mexican Planchas

de Plata silver strike in 1736. In response to repeated raids, in 1748 the

Spanish made a formal declaration of war against the Apache.

In 1752, because of continued Apache raids (and the Pima revolt of 1751), the

Spanish built the first permanent garrison (presidio) in southern Arizona at

Tubac.

From 1786 to 1793 the Spanish worked hard to establish peace treaties with the

Apache. Some Apaches settled in rancherìas (“peace establishments”) near the

presidios where they were taught to farm and received rations. Sporadic Apache

raids continued however, interfering with mining in southeastern Arizona.

The Apache were generally peaceful during the first ten years of Mexican

independence (starting in 1821). But, when deteriorating economic and political

conditions caused Mexico to discontinue rations at the peace establishments, the

Apache resumed raiding again. By the late 1840s, much of the Santa Cruz valley

had been abandoned by Mexican ranchers, settlers, and miners.

After Oro Blanco became part of the U.S. with the Gadsden Purchase in 1853, the

Apache continued to cause trouble for American miners in southeastern Arizona.

The Apache regarded the miners and other settlers as intruders on their lands.

The “Indian problem” was lamented in Mining and Scientific Press in 1871:

“Mining in Arizona experiences considerable difficulty in carrying on business

on account of the Indians. The troubles on that score seem to be increasing

instead of diminishing as was expected by the gradual increase of population.

Miners have no chance to prospect on account of the danger of attending trips at

any distance from the settlements. People in Arizona are not free to go where

they please as in other countries for fear of molestation from Apaches. They

have to stand guard over their stock and other property. It is necessary for

escorts to go with every wagon and team on its journey, and the miners and

prospectors are compelled to move around in parties to protect themselves from

their wily foes. It is to be hoped that these obstacles will shortly be

overcome, and the large extent of mineral country, now lying idle and useless

will be accessible to enterprising pioneers who have settled in that remote

territory.”

To protect Americans exploring and settling in south-central Arizona, the U.S.

Army established military garrisons on each side of the Santa Cruz River. These

garrisons included Camp Moore at Calabasas, just north of Nogales, and Fort

Buchanan, near the present day town of Sonoita.

Starting in 1861, the U. S. Civil War drew soldiers away from these military

garrisons. This left the few American mines, e.g., Charles Poston’s Cerro

Colorado silver mine, unprotected from the Apache and marauding Mexican bandits.

Miners virtually abandoned their workings to the north and east of Oro Blanco.

When the Civil War ended in 1865, the Army returned to Arizona. With higher

prices for silver, miners came back to their diggings.

But Apache raids continued until 1886, when famed Apache warrior, Geronimo,

finally surrendered. Just before Geronimo’s surrender, Apaches caused havoc in

murderous raids on the ranches of A. L. Peck and John Bartlett near Ruby. (For

the details of these two incidents, see our column of December 26, 2003.)

Thirty years later, Yaqui Indians, political refugees from Sonora, Mexico,

became a complicating factor in U.S.-Mexico border relations. In February 1917,

the U. S. 10th Calvary, made up of African American troopers, occupied

detachment camps in Arivaca and the village of Oro Blanco. The soldiers also

manned a troop outpost in Bear Valley, a few miles east of Ruby and patrolled

south-central Arizona on a regular basis.

According to 10th Cavalry Lieutenant H. B. Wahrfield, the Yaqui used a

border-crossing trail through Bear Valley to smuggle arms and ammunition to

their Mexican tribesmen who had for some time been in revolt against the Mexican

government. Yaquis would sneak across the border, work in U.S. mines and on

ranches to accumulate money, then purchase rifles and ammo and return to their

people in the Yaqui River section of Sonora.

The Yaqui had long lived in northern Mexico and always fought vigorously against

anyone trying to subjugate them. This included the Spanish Conquistadors and

successions of Spanish and Mexicans groups. From 1916 to 1929, the Yaqui-Mexican

conflict became a full-scale war, leading to the final defeat of the Yaqui in

1929. During this period, the Yaqui raided and robbed mines, ranchers, small

settlements, and the railroads – all in Mexico, not the United States. The main

source of weapons, ammunition, and money to support their activities came from

Yaqui working in the U.S. Bands of Yaqui frequently crossed the border from

Mexico to secure needed supplies in the U.S. to continue their battle against

Mexico.

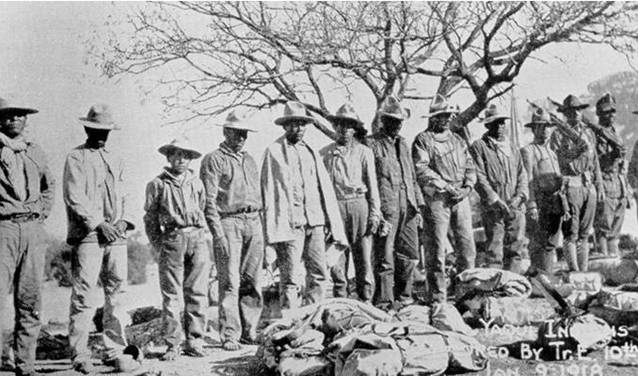

On January 9, 1918, a group of about 30 Yaqui, traveling on foot through Bear

Valley, ran into a group of 10th Cavalry troopers. The Yaqui apparently mistook

the black soldiers of the 10th Cavalry for Mexican soldiers and opened fire.

Following a short fight, U.S. troopers captured ten Yaqui, including an 11-year

old boy. There were no American casualties; however, one of the captured Yaqui

received a serious wound. Approximately 20 Yaqui escaped. The U.S. cavalry took

the 10 prisoners to headquarters in Nogales. The wounded Yaqui died just before

arriving.

A month later, the remaining nine Yaqui faced legal action in U.S. District

Court in Tucson. Officials dropped the charges against the young boy. The judge

indicted the eight Yaqui adults for “wrongful arms exportation.” They served 30

days in Tucson’s Pima County jail.

The Military Governor of Sonora, Mexico attempted to extradite the Indians for

prosecution by the Mexican government. U.S. District Judge William Sawtelle was

apparently somewhat sympathetic to the Yaqui position and feared that

extradition would lead to their quick execution. The sentence he handed out

precluded any possibility of deportation.

(Sources: Marshall Trimble, Arizona – A Cavalcade of History, 1989; John P.

Wilson, Islands in the Desert - A History of Uplands of Southeastern Arizona,

1995; Mining and Scientific Press, 1871; Major Albert G. Scooler, “Cavalry’s

Last Indian Fight, Armor, 1970; Nogales Herald)

|

Captured Yaqui Indians Tenth cavalry troopers captured 10 Yaqui Indians after a short fight near Ruby in 1918. (Photo courtesy of Tenth Cavalry and Border Fights, 1964) |

Next Time: Ruby’s Poet Laureate Charlie Foltz Back to List of Columns