Column No. 56

ALONG THE RUBY ROAD

Wayne Winters’ Battle with the Jolly Green Giants

Bob Ring, Al Ring, Tallia Pfrimmer Cahoon

For more than half a century, Wayne Winters was a printer and both editor and

publisher of a number of small country newspapers in the west, including the

Tombstone Epitaph. Winters was also a miner, so knowledgeable that he wrote

successful books about mining. Here is the story of Winters’ battle with the

Jolly Green Giants, the name Winters gave to the U.S. Forest Service.

In the 1960s, with southern Arizona’s borderland Montana mine shut down and its

Ruby mining camp rapidly becoming a ghost town, mining in the rest of the Oro

Blanco area struggled to stay alive. The struggle was particularly difficult for

miners with unpatented (no title to the land) mining claims on Coronado National

Forest land.

In the early 1960s the U.S. Forest Service took notice of all the individually

held mining claims and associated buildings that peppered federal lands.

Supposedly concerned that this hampered effective forest management, the

Supervisor of the Coronado National Forest, Clyde Doran said that, “Most of the

miners are just looking for a free summer cabin on National Forest Service

land.” The Forest Service’s premise was that many miners had no intention of

mining their claims.

According to federal law of the early 1900s, a miner could stake a claim on

federal land, but he must work the mine enough to show that he had a “valid”

claim, defined as having enough minerals to cause “a reasonable and prudent man”

to expend his time and money developing the mine.

By the mid 1960s the U. S. Forest Service had mounted an aggressive campaign to

challenge many of the unpatented Oro Blanco claims; drive “invalid” mining claim

holders off their properties, and bull-doze and/or burn all man-made structures

thereon. The Forest Service also sealed mine shafts. Rationale for these

controversial actions included "safety" and to discourage settlement by

transients, during America’s “hippie” period. The Forest Service literally

kicked small miners off their claims if they couldn’t prove that they had a

moneymaking mining operation.

The battle between the Forest Service and small miners in the Oro Blanco Mining

District makes for fascinating reading in the newspapers of Southern Arizona in

the 1960s and 1970s.

Wayne Winters, at the time the editor of the Tombstone Epitaph, owned the Oro

Escondido (hidden gold) placer mine about three miles south of Ruby, just a mile

north of the international border with Mexico. The Forest Service claimed that

the mine could never be a moneymaking proposition. Winters fought the Forest

Service and the Bureau of Land Management for years in the courts and in his

newspaper. He charged the Forest Service with a “systematic policy of harassment

against small mining operations on forestlands.” In article after article in his

Tombstone Epitaph, Winters ridiculed the efforts of the Forest Service and

variously referred to them as the “Greenies,” “Boys in Green,” “The Green

Plague,” “Chuckling Green Giant,” “Jolly Boys in Green,” and “Brutes in Green.”

Never losing his sense of humor during the long litigation, Winters relocated

his gold mining claim, renaming it Doran’s Folly, after the head of the Coronado

National Forest.

But the courts eventually decided in favor of the Forest Service. In a final

“nose thumbing,” Winters wrote into his will instructions that his body be

cremated and his ashes be spread over his former mining claim. In a 1984

interview with Sam Negri, Winters said “I’m going to be there when the Forest

Service is not,” relishing the feel of this posthumous victory.

Wayne Winters was born on October 16, 1915 in Council Bluffs, Iowa. He graduated

from high school in 1934, but had no interest in attending college. His father

helped him get a job as a printer’s apprentice on the Council Bluffs newspaper.

Winters became a talented journalist and taught journalism in Florida.

Moving to the southwest in 1946, he bought and published the Douglas Budget in

Wyoming. In 1949 Winters sold the paper and arranged a contract to set up the

mechanical plant for the Casper Morning Star, also in Wyoming.

In 1950 Winters bought the Grants Beacon in New Mexico. In Grants, Winters’

interests broadened from journalism to mining. Tombstone Epitaph reporter Edina

Strum wrote, “He taught himself all there was to know about mining, then started

buying mines and writing about the industry. … His best selling book, ‘How to

Pan for Gold,’ sold 250,000 copies.”

After he left Grants, Winters hooked up as editor of the Prescott Daily Courier

and later spent six years in the composing room of Tucson Newspapers, Inc.

Finally, in 1965, Winters moved to Tombstone and became editor of the Tombstone

Epitaph. It was during this period that he had his battle with the U.S. Forest

Service over mining in the Oro Blanco area. When he left the Epitaph in 1975,

Winters founded a monthly newspaper, Western Prospector and Miner, which he

published out of his home in Tombstone for the next decade, while continuing to

write books about mining.

Wayne Winters died at the age of 81 on December 7, 1996 in Sierra Vista after a

long illness. Winters was remembered by his wife Viji “as a man with a great

sense of humor who was kind and generous.” A tall, slow-talking man, Winters

enjoyed working alone, looking to avoid controversy, but managed to attract

adversaries, like the Forest Service. In his 1984 interview, Sam Negri wrote,

“He is accustomed to direct action and believes in retribution.”

|

|

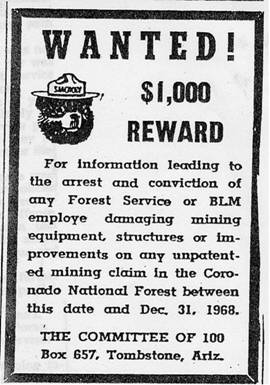

This is one of many newspaper “appeals” for information on

Forest Service harassment of small miners. (Photo courtesy of the

Tombstone Epitaph, 1967) |

|

|

For more than half a century, Wayne Winters published

small country newspapers in the west, including the Tombstone Epitaph.

(Photo courtesy of the Tombstone Epitaph, 1985) |

(Sources: Arivaca Briefs; Tombstone Epitaph; Arizona Republic; Arizona Daily

Star; Sam Negri, “Strong-willed Tombstone Publisher,” Arizona Republic, 1984;

Edina Strum, “Epitaph Editor Remembered,” Tombstone Epitaph, 1997)

Next Time: George B. William’s

Life-Long, Long Range Love Affair with Mining

Back

to List of Columns