|

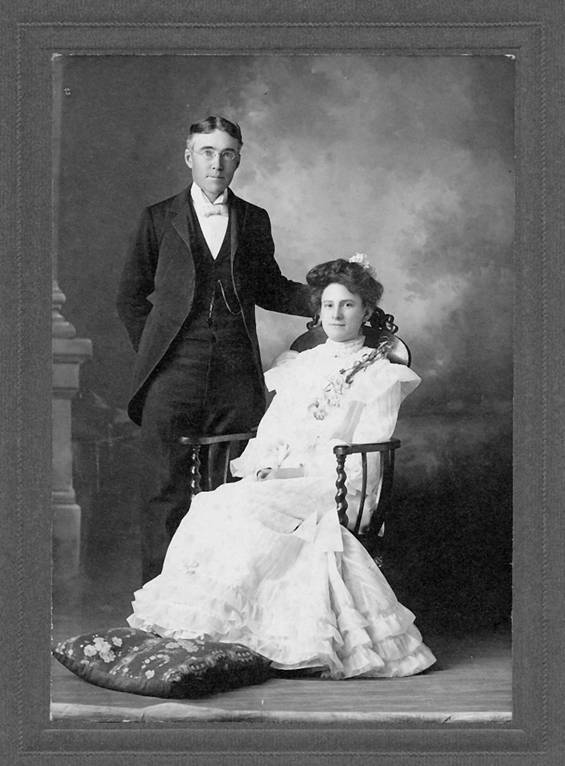

Wedding Portrait |

Column No. 71

Bob Ring, Al Ring, Tallia Pfrimmer Cahoon

This column continues the life story of Ines Fraser, widow of Jack Fraser, who

along with his brother Al, was brutally murdered by Mexican bandits in the

February 1920 robbery of the general store at the Ruby mining camp. We are

telling the story in Ines’ own words, in a long letter written in 1968 to her

grandson Bruce and her granddaughter-in-law Claudia:

Now my dears, let me get back to my love story. I must admit that the age

difference between us (Jack was 40, I was almost 23) gave me pause. But, I knew

the right man when I saw him! By December 4th [1902] we were engaged and my

Solitaire had arrived (mail order) and everybody knew and talked about it. Next

morning, when I reached the schoolhouse [at the mining camp in Liberty,

Colorado], the children were chanting: “Teacher got a marriage ring,” over and

over so I let them admire it in the sunshine, to see the prismatic glisten of

the small diamond. They had watched or heard of the arrival of the package at

the post office.

Jack subscribed for half a dozen magazines for my birthday and Christmas. Among

them were the Art Magazine, Atlantic Monthly and Burr McIntosh photographic

monthly, then the most praised and circulated publication of its kind, and

“Etude,” an excellent music review, containing several excellent piano and voice

“pieces,” sheet music size each month. He said that one reason for these was

that he had to leave me for some months to investigate mining prospects in the

southwest.

That year I spent my Christmas holidays in Crestone [Colorado], where Papa had

been sent as engineer for the one daily round trip from Moffat, on the main

railroad line, through the San Luis Valley from Salida to Alamosa. The trip by

stage (a farm type wagon) was no easy 14 miles, especially during the winter,

and it was a compliment to me and my parents when Jack hired a “rig” from

Duncan, a deserted camp, near Liberty, to come to see the family and take me

back to Liberty. It was artic cold, at the 8,500 feet altitude, and the trip was

slow even with a light weight carriage. The road went over sand ridges and sandy

“bottoms” in between, higher than the 8,500 feet, I mentioned, to avoid worse

sand conditions lower down toward the Valley. Luke Kellogg, who was the owner of

the team and carriage, still lived alone in the abandoned camp. He had kept

everything in good shape and provided plenty of fur and heavy woolen robes.

Jack left in January for Arizona where he had charge of the site of some mines,

and sure ‘nuff, he was gone nearly a year. This meant that our real “courtship”

was by letters. They were daily most of the time, though mail in that part of

Arizona was only twice or three times a week. His letters were absolutely

wonderful, not only as love letters, which were unexcelled even in literature,

but were filled with anecdotes, descriptions, quotations in poetry and prose,

parodies on many familiar verses and songs, allusions and quotable phrases from

English authors. I had learned a good deal about some of these topics, so I

could, I think, respond with some pleasure and satisfaction to both of us.

During the year that Jack was in Arizona, the branch railroad line from Moffat

to Crestone was discontinued and papa and his crew were sent back to Salida, so,

of course, the family came also. After returning to Salida, papa had a few

health problems so he retired from the railroad and began a second part-time

career assisting the Salida city government.

Jack returned from Arizona in January and we were married a short time after on

January 26, 1904. Our wedding was held in the evening at our family home in

Salida. It was very simple with just 25 guests, mostly family and near friends.

My pastor, E. S. Plimpton, from First Baptist Church performed the ceremony.

We had gathered huge ferns in the mountains the summer before, pressed them and

pinned them to the bare curtains on the day of the wedding; and we had a few

carnations from the “green house” and some smilax. Papa had earned good wages as

a railroad engineer, and Mama was a good manager, so we always had plenty of

good things to eat and wear, good furniture and carpets, a home bought and paid

for, etc. but nothing for “show” or just to impress “the Jones.” My trousseau

was lovely, complete and costly in materials and home and hired seamstresses,

and my hope chest had the conventional hand-hemmed and, embroidered linens and

some silver.

A group of boys, headed by my brother Forrest tried to duplicate the old

fashioned raucous shiveree of Mama’s time, demanding treats. Mama let them have

a good deal of our wedding supper, and my new husband gave them five dollars to

stop their racket. They adjourned to Forrest’s room to eat, and we had no more

noise from them.

Now my dears, I jump to tell you that during Jack’s year in Arizona, he made a

good “deal” in the sale of some mines, getting a commission sufficient to

warrant his getting married. After he returned to his camp near Liberty, Jack

fitted up a cabin for me, putting in a fireplace, for one thing, and having Al

move to another. They had been living together except when one or the other was

away.

We went by narrow gauge, “accommodation” train (mail-car, several freight cars,

one passenger car) from Salida to Moffat, in the San Luis Valley, changed to the

shorter train from there to Crestone, met the “Stage” there to go to “our” camp

on Pole Creek, near Liberty. Mr. Diamond, the “stage driver,” had arranged for

someone to meet him at Duncan, the almost deserted place where Pole Creek sinks

into the sands, to take the mail (horseback) on to Liberty, while Mr. Diamond

took us up the canyon to our camp - about three miles. About half way up, we

stopped at the one house there was, and warmed up a while. This was the home of

“Old Cale” Frazier and his wife. It had been bitterly cold ever since leaving

Crestone, and, as the road was in heavy sand, the trip was slow.

The horses had to scramble over frozen ruts and rocks and icy water from “Old

Cale’s” on up! The “stage,” you see, was just a wagon with two seats clamped to

the sideboards - high enough to give us all the wind that was there to pierce

us.

Well, by and by, we heard the boom of Al’s “torpedoes” and dynamite caps, which

he set off as we approached. “Welcome to the Bride?” Unloaded trunks and other

things, paid Mr. Diamond, and he, poor man, had to go down that creek and across

to Liberty late at night! He afterward said that he would never have made that

trip for anyone on earth but “little Jack Fraser.” (Jack was little Jack to most

people.)

Now dears, I’ll jump again, and answer a part of another bit of your curiosity.

We stayed at the Liberty camp till about May, when Jack had a chance to start

some mining business a few miles from where he had been in Arizona. He had

investigated the placer conditions to the south and had taken up several claims

in gold bearing gravel. Jack was going to try some development, but needed

capital, for in that arid land, dams were needed for any but short-season placer

work. The canyons were dry except during the summer rains.

So he and a few others from Liberty formed a company and engaged long-time

family acquaintance, Gene Alnut, as a “promoter” to sell stock to get started.

Jack went back to southern Arizona and set up a camp, hired road mending, and

shipped in some supplies. I returned to Salida. Finally, that summer, Jack sent

for me to join him at Los Alamos camp, two miles from the Mexican border in what

was then the Territory of Arizona.

(Sources: Fraser family records, courtesy of Connie Fraser Kiely)

|

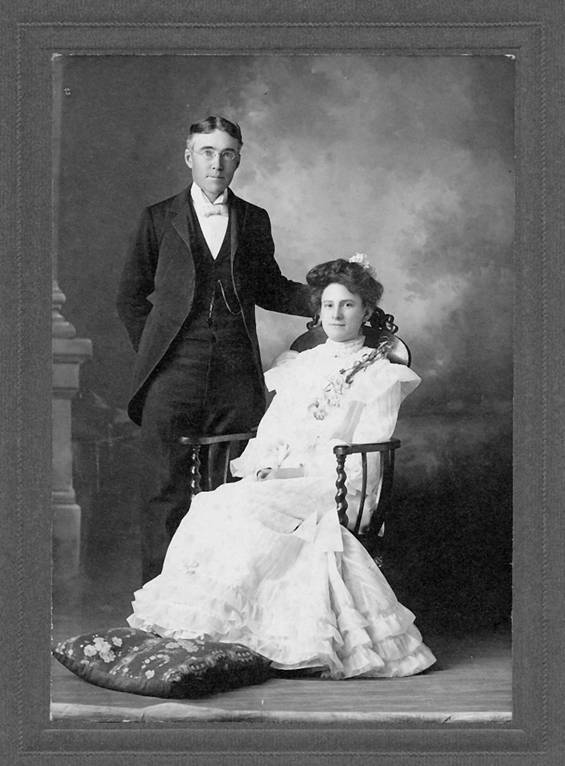

Wedding Portrait |

Next time: Ines Fraser’s Trip to Arizona: Liberty to Arivaca