This column continues the life story of Ines Fraser, widow of Jack Fraser, who along with his brother Al, was brutally murdered by Mexican bandits in the February 1920 robbery of the general store at the Ruby mining camp. We are telling the story in Ines’ own words, in a long letter written in 1968 to her grandson Bruce and her granddaughter-in-law Claudia:

So, Bruce and Claudia, my adventure to the desert southwest was about to begin! Except for one Christmas trip back to Mama and Papa’s hometown in Parsons, Kansas, and my time in Boulder at the University of Colorado, I had never been more than 50 miles from Salida.

I had been at home, in Salida, while Jack had gone to Arizona to set up the Alamos mining camp, 70 and more miles south of Tucson. I left in August of 1904, going south from Salida to Pueblo on the Denver and and Rio Grande Railroad. I changed trains there, after a layover of several hours and was able to visit friends till train-time. There too, I met brother-in-law Al, and the promoter of the [Arizona mining] project, Gene Alnut. We had another long stop to change trains to Deming, New Mexico. We suffered both the desert heat, plus the extra heat of railroad yards and machine shop.

We stayed right there, at the railroad hotel, took rooms upstairs and spent the day in the hotel “parlor,” where I played the piano, Gene got out his flute and I sang - hot and “dripping,” till the lovely big clouds gave us shade. I went to a window to enjoy them -scattered masses, blue sky in between and saw the phenomenon of five separate “let downs” of rain, while there was none in Deming! But one mass arrived and dumped thousands of gallons of water right down on the town. It is unbelievable, I think, to anyone who has not seen a local, not too extensive cloudburst!

Our stay in Deming was lengthened, because the railroad beds were under water and it was unsafe for trains to go on to Tucson. Gangs of “section men” began to work as soon as the rain stopped, and had the tracks safe but precarious by night, and our train crawled out, men ahead testing tracks and roadbed. Water was still like lakes on both sides until we reached an area beyond the big “he rain.”

We reached Tucson in midmorning. No rain there. Jack had rooms for us at the old San Augustin hotel. This had been a church, with inner courts and cloisters, thick, thick walls and patios with plants and trees. The only modern things were electric lights - single bulbs, turned on by pulling a string - and bathtubs and toilets. I spent the afternoon in the tub, getting out to put on a kimono and getting into the tub again. The men were downtown, buying supplies and arranging for transportation. Jack had been in town several days, so these final preparations went along well.

Evening came, with comparative coolness. We went to eat at the Merchants Café, and watched the town “come to life.” Stores were open; the saloons and gambling places were noisy, and they remained so all night, I think. The noise of clicking poker chips, roulette wheels, shouting and singing penetrated the San Augustin with its thick walls and comparative seclusion, away from the main street. I was too warm to sleep well, but the noise was the chief thing I remember.

Up early, breakfast at 6:30. People sprinkling and sweeping sidewalks in front of the already open stores. We were ready to go! The route was south from Tucson to Arivaca Junction, then southwest to Arivaca, from there southeast to Oro Blanco, and finally south to Warsaw camp and Old Glory Post Office at the end of the line.

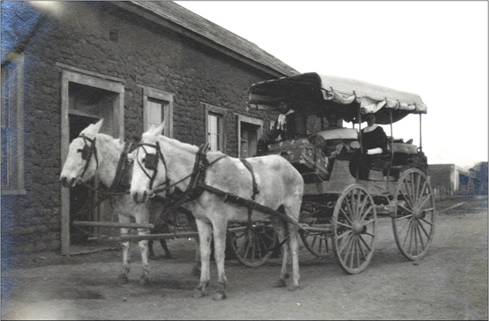

I cannot entirely describe the vehicle, though it was called a stage. It was built high, had three seats and large space for luggage, “ribs” every two feet, to attach canvas in case of need; a canvas top stretched tightly. The stage company used horse or mule teams to pull the stage and changed the team several times en route to keep up a gallop or fast trot pace.

“Old Man Leatherwood” had agreed to be the driver for the trip, though he no longer drove the stage out to the mining camps. I found out that Robert Leatherwood was a well known Arizona pioneer as well as a very colorful character, now sixty years of age. Born in North Carolina, he came to Tucson in 1869 after the Civil War, during which he was a scout for the Confederate Army. In 1873 he located the first American gold mine in the Oro Blanco district, where we were headed. Besides his part-time mining, Leatherwood spent 20 years in politics including mayor of Tucson and Pima County Sheriff. I’m sure that one of the reasons that Jack picked Leatherwood as our driver was Leatherwood’s physical stature; he was five feet five inches in height, only one inch taller than Jack, with a reputation for being feisty and fearless.

We were underway! The mountains were beautiful; the road for several miles was good, though unworked, for it was on firm, slightly sandy ground. We passed Mission San Xavier, then closed and not yet restored. The old church founded in 1692 and its quadrangle of cloisters, had stood the pillage of Apaches and ravages of time pretty well. Many of its sacred relics were mutilated, and the place had had to be repaired frequently, but its position, its structure, its history, all made it most beautiful and interesting.

When we reached the “Junction,” a stage rest stop at the turnoff for Arivaca and the borderland mining country, it had just stopped raining and everything looked cool and clean. I forgot to tell you that Arizona had had a two-year drought which had broken in July, just a few weeks before I went there. The stench of carcasses was pretty bad for part of the journey, but at the Junction, there had not been so many cattle, and the horses had been fed in the corrals and stables with stored hay and grain. The revival of grass and foliage had been rapid and wonderful, and many of the trees were in bloom. The Junction was a settlement of the stage station and a few ranches.

“Old Smith” had been running the station for ages. His wife, a lovely Mexican “Senora” in her sixties, fed stagehands, ranch and horse-tenders and whatever mining men and travelers came. Sons were overseers and bosses, and did some mining. The house was a long row of separate rooms, each one opening onto the veranda. The back of the building was the hill, gouged out and leveled to make room for house, veranda, and a narrow rose garden.

Mr. Smith was a “character” - smoked many cigars each day and had his regular pint of whisky as he had done all his adult life; witty, interesting, wise, happy and prosperous. I understand that the big Flu epidemic took him a few years later. Mrs. Smith lived several years - the boys sold the ranch, the stage-contract, and all, I believe and moved into Tucson.

The miles from the Junction to Arivaca were over rolling country, with good “natural” roads – but not good at the arroyo crossings. Our stagecoach had to wait on the brink of a steep-sided, narrow-bottom arroyo till the rush of water from a flash flood quieted down and decreased until the stage team could safely descend and scramble like fury up the opposite bank, slippery after the rain. The driver had to know his business and Arizona “flash floods” and how to urge his horses up the steep “other side.” No one but an experienced teamster like old Leatherwood, and strong, obedient horses, used to the roads, could possibly have taken heavy loads up and down those arroyo crossings during the rainy season.

As we neared Arivaca, the road passed close to Twin Buttes and Cerro Colorado, where mining had been carried on for many years, and head frames, mining equipment and some appearance of activity showed that, although the mines were no longer rich and productive, they were not deserted. Cerro Colorado, dark red and beautiful, was owned by the Udall brothers, who also had ranches and other interests. I think that Stewart Udall, who was Arizona Congressman and, later, Secretary of the Interior and a fine “Conservationist,” was a son or grandson of one of those Udall brothers, but I am not sure.

At the town of Arivaca, the landscape was open and fairly level, and there was an almost permanent stream, with, at this time, fresh green foliage after the long drought, and fine large trees, many of them in bloom. Birds were abundant - and tuneful, as if it were spring instead of August.