Column No. 74

ALONG THE RUBY ROAD

Life at Los Alamos Mining Camp

Bob Ring, Al Ring, Tallia Pfrimmer Cahoon

This column continues the life story of Ines Fraser, widow of Jack Fraser, who

along with his brother Al, was brutally murdered by Mexican bandits in the

February 1920 robbery of the general store at the Ruby mining camp. We are

telling the story in Ines’ own words, in a long letter written in 1968 to her

grandson Bruce and her granddaughter-in-law Claudia:

I’ll begin the story of my life in the “wild west” of territorial southern

Arizona with some memories of my first few years in Los Alamos mining camp. Keep

in mind, my dears, that this was the period before I started having children.

For the most part, Jack and I lived at Los Alamos. Jack was busy with mining

activities, at first only in the Oro Blanco district in southern Arizona, but

later extending to exploration in Nevada and even into northern Mexico. Of

course Jack and his brother Al also maintained close ties to their mining

interests in Colorado.

Looking back at these times, I’ll say only that it was all amazing, interesting,

and not real hardship, though we lived in tents for nine months after my arrival

- until we built the big adobe house.

Early in my residence in Los Alamos camp, Jack, “Don Chapito” to the Mexicans,

began making me a more independent person, for he said his duties would not

allow him to be with me a good share of the day and he wanted me not to have to

stay right at the camp. He did take time for some walks to show me various

landmarks and trails which I could go on alone, later.

Jack taught me to mount a burro by myself, and then to do the saddling and

bridling alone - and I did not like that! I had always had my men folks to

attend to all courtesies expected or requested about my things, but it was not

too long before the task did not seem so bad. I could go further than I did

before; the burro was tractable and his slowness did not bother me a bit. It

just took away fear of being unable to check him if I decreed.

Then I graduated from burro to pony and, in the early evenings Jack and I could

ride down the Alamos Canyon at a trot or gallop, for the gravelly bed widened

and made good going for about a mile and a half. Alazan, the pony, had a mind of

his own and soon found out that he could be “boss,” would stop on a steep trail

and puff and even groan, take a few steps and repeat, and my small quirt and the

child's spurs did not help get us to the top, so I’d get off and lead him.

From a rise when the descent was steep, he stood and looked back at me till I

would dismount and lead him. But when Jack used him to go for the mail, Alazan

went along as continuously as if the trails were on the level. This went on for

quite a while. Horses and mules and burros at camp were let loose at night to

feed on the slopes and ridges, some being hobbled and some free. Alazan was a

free one. Fortunately I was never supposed to be “independent” enough to go

after him myself. We had boys hired to do that, and Alazan was a “terror” at

times, dodging, running, making a lot of fun for observers but not for the boys.

I watched the performance one morning, and when I saw Alazan running at

race-horse speed all the way up a hillside, I made up my mind that he should not

bully me any more - and told him so at his next puffing and blowing. With my

more confident voice and manner after that, I never again had to wait a long

time for him to get his breath and did not dismount. I did continue to lead him

down very steep places, though.

In the meantime, between jaunts, I studied Spanish and practiced talking with

Mexican workers when they came to our camp store. I learned from them the

Spanish names of the trees and other vegetation around us.

Some of the things I was used to eating while growing up in Colorado were in

short supply at Los Alamos. Fresh meat was very hard to obtain, and almost

impossible to keep during warm weather. Until we got a garden producing,

vegetables were likewise unknown. So when you eliminate meat and vegetables from

your diet, as Jack said, “The resultant meal is liable to be sort o’ slim.” But

such is life on frontier; we made the best of what we had.

Bruce and Claudia, in your last letter, you used the expression “very few women”

at the Alamos camp. Let me tell you that I was the only resident white female in

all the years I spent at Los Alamos camp, and had no over-night visitors for

years! And then only a ten year old girl who came home with me from the old

border camp, Oro Fino, a few miles beyond the Warsaw mine (known legally as “Old

Glory” where the stage line from Tucson ended). Also, I had one teenage girl

from Oro Blanco for a day or two.

While the camp was active we had various cooks, and I had a Mexican laundress at

times. The Mexican women were not there much of the time. I don’t think that you

young people, city or town or even farm living, can picture the isolation, the

quiet, the often waterless camp, nor the happy contentment that was mine.

You might wonder what I did with my time. All sorts of things; I even helped a

little with the mining. I remember helping to build a dam in a shallow wash.

Often I would be the “lookout” as Jack opened a connection upstream to see if

our dam or sluice systems were working properly. I picked up broken cement

blocks and piled them. I picked up and piled lumber scraps. I did a little

painting – a red wagon as I recall. I gathered flower seeds and decided where to

plant them. And I put a lot of work into our vegetable garden! For amusement, I

collected, sorted, and rearranged pretty rocks.

There were periods when Jack and I were the only people in camp and had no horse

or mule or burro. We walked the five miles for the mail, often waiting till

nearly sundown to avoid the heat, and coming home by moonlight; but I stayed all

alone sometimes and Jack went alone for the mail, which was often late. He would

start early, expecting to return before real dark, and the stage would be late!

I confess that we quit these habits before I had been left alone many times! I

was not as surefooted as Jack, and the canyons were dark even on moonlit nights,

so we went the day after the mail came in or, if it was hot, I did not mind

staying, in daytime. (We often went only once a week. The stage came three times

a week, usually).

I remember one time that I became very tired of being among so many men, and,

when I expressed myself about it, Jack took time off and went with me to the

little village of Oro Blanco, he walking and I riding Alazan. It is only five

miles, but over such terrain that women-folks don’t indulge in much visiting if

any.

Of course Yank Bartlett’s daughters, Tula and Phoebe, who I had met on my first

trip into the area, were happy to have me! They had a boarder now, a California

girl who was teaching at the Oro Blanco school. What a talk-fest we girls had!

We sat up till “all hours” and enjoyed every minute. I stayed two days and then

Jack brought Alazan and I went back to camp much refreshed.

|

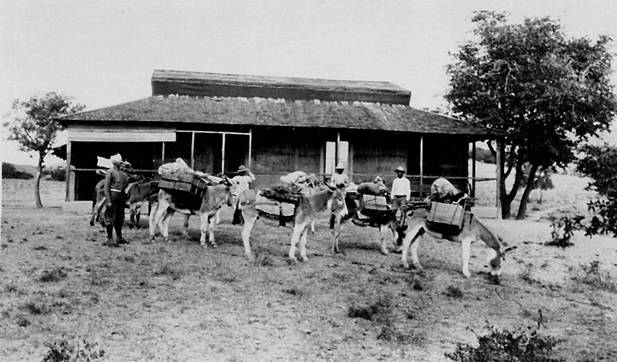

After nine months living in tents at Los Alamos, the

Frasers built this large adobe house on a concrete foundation. A mule

train, loaded with supplies from Tucson, has just arrived. (Courtesy

Connie Fraser Kiely, circa 1910) |

|

|

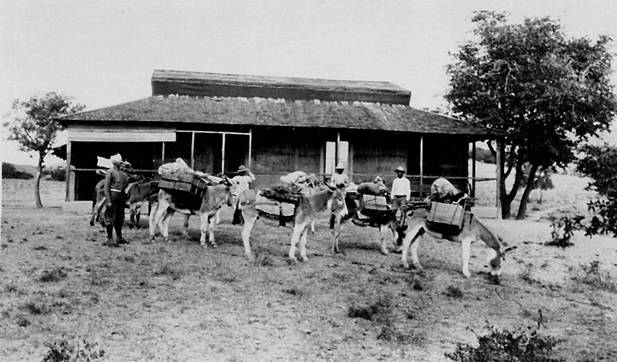

Ines Fraser adds promising soil to the gold-separation

sluice at Los Alamos. (Courtesy Connie Fraser Kiely, circa 1910) |

Next Time: My Horseback Adventure to Nogales

Back to List of Columns

(Sources: Fraser family records, courtesy of Connie Fraser Kiely)