Column No. 9

ALONG THE RUBY ROAD

A Difficult Life in the Early Oro Blanco Mining Camps

Bob Ring, Al Ring, Tallia Pfrimmer Cahoon

In the 1870s and 1880s, despite the danger from Indians and the hardships of the

environment, the Oro Blanco hills filled with mines, camps, and people. There

were far more Mexicans than Americans and probably more miners than farmers and

ranchers.

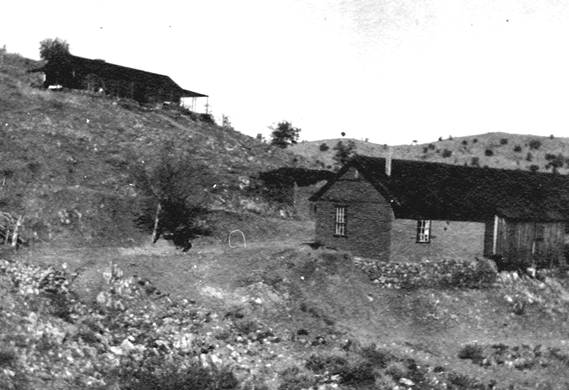

As mentioned in an earlier column, the small village of Oro Blanco emerged in

the mid 1870s to support the increasing number of people. (Oro Blanco village

was along today’s Ruby Road, about four miles northwest of Ruby.)

By the early 1880s, over 200 miners lived in the village of Oro Blanco.

Buildings of wood and adobe began going up. One enthusiastic writer described

the village in the October 11, 1880 edition of Tucson’s Daily Arizona Citizen:

Oro Blanco is a quiet little town, inhabited by a superior class of miners and

workmen, and all are opposed to sharps, tramps, and jumpers. They are an

intelligent class generally, and are determined to keep a model mining camp,

free from loafers, rowdies and reckless characters. The mining claims are

numerous, and show prospects that will soon bring capital among them.

The Montana mine also attracted a significant number of miners by the mid 1880s.

A small mining camp, named Montana Camp (forerunner of Ruby), started growing at

the foot of Montana Peak.

By the late 1890s and early 1900s, the larger mining camps – including Montana,

Oro Blanco, Yellow Jacket, Austerlitz, Warsaw, and Old Glory – had populations

of up to 50 people. And there were familiar (though crude) hallmarks of

civilization, like stores, post offices, schools and cemeteries. Virtually every

mining camp had at least one saloon. Perhaps not surprisingly, there is no

evidence of churches.

Housing ranged from a few adobe buildings, to frame buildings, to wooden shacks,

tents, and even caves. A few mining camps had crude boarding houses. Warsaw Camp

boasted about the “El Warsaw” hotel (Tucson newspaper ads exaggerated its

accommodations). Bob and Al Ring’s paternal grandparents, Ambrose and Grace

Ring, lived in the “El Warsaw” for several months in 1905/06. (See the photographs and our next column for their story.)

The mining camps were a true melting pot of humanity. Anglos, who typically ran

the mines, were relatively few in number. To keep costs low, Mexicans did most

of the underground mining. A few Chinese worked as cooks or housekeepers and a

group of Japanese grew vegetables to sell to the mining camps.

Life in the mining camps during Arizona’s territorial years was harsh, but

people came and worked hard, drawn by visions of wealth and the challenge of the

mining. They came from Mexico, France, Ireland, England, Japan, China, and of

course the U.S. Some of these people were prominent pioneers of early Arizona.

The list includes soldiers, Indian fighters, doctors, bankers, cattlemen,

teamsters, sheriffs of Pima County, mayors of Tucson, and governors of Arizona.

Others, including Ambrose and Grace Ring, came not seeking riches, but just to

work at the mines. They were not well known people, but worked just as hard

under very difficult conditions.

Travel to the Oro Blanco mining camps at the turn of the 20th century was

certainly an adventure! Regular stagecoach service from Tucson to the Oro Blanco

mines began soon after the completion of the transcontinental railroad through

Tucson in 1880. The stagecoach trip was 70 miles over rough dirt roads.

A stagecoach schedule from 1905 shows a buckboard stagecoach leaving Tucson

three days a week for Arivaca, Oro Blanco village, and the mining camps. The

stage departed at 6:00 a.m., traveled south to Arivaca Junction (passing right

through today’s Green Valley), and then west to reach Arivaca by 2:00 p.m. The

mines were two additional hours to the south. The horse or mule teams that

pulled the stagecoach had to be changed seven times to keep up a gallop or fast

trot pace.

There is evidence of active social life in the mining camps. The Weekly Arizona

Enterprise described an 1891 Christmas party at Oro Blanco, with 100 people

attending from Arivaca and the nearby mining camps. The party included supper

and dancing, and lasted all night.

Arizona Historical Society photographs document well-attended picnics held in

the 1890s, with people from Arivaca and the Oro Blanco district.

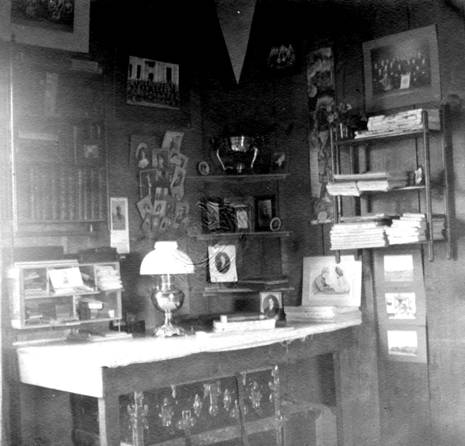

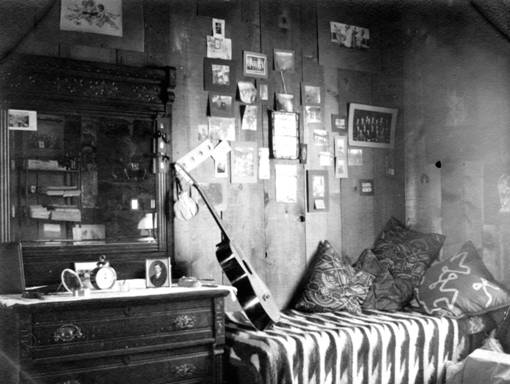

If life was tough in the camps for the miners, think of the women. If a wife

joined her husband in the camps, she had to accept the wild untamed surroundings

with little or nothing to set up a home. Clean water was hard to find and there

was no sewage system. The hardships of poverty, drought, fire, and Indian

attacks were real. Finally, a wife had to be ready to pack up and leave when the

ore played out and her husband moved on to the next mining camp.

The women who endured these hardships had an important positive impact on the

mining camps. They organized and ran the schools and social events. Women

established livable conditions to provide as many refinements as the environment

allowed.

Yes, life in the Oro Blanco mining camps at the end of Arizona’s territorial

years in 1912, was certainly difficult. Talking about Montana Camp, but equally

valid for its neighboring camps, author Carol Clarke Meyer wrote:

A few of the men of the neighborhood had their own diggings, but many worked for

others. Wages were small and money was scarce. Some families lived in adobe

huts, but many had only tents or even occupied caves. Everybody worked hard but

there was little to relieve the grimness of the struggle.

(Sources: Carol Clarke Meyer, “The Rise and Fall of Ruby,” The Journal of

Arizona History, 1974; Phil Clarke “Recollections of Life in Arivaca and Ruby,

1906-1926,” Arizona Historical Society; Gazetteer and Business Directory, 1884;

Daily Arizona Citizen; Weekly Arizona Enterprise; Anna Domitrovic, “A Woman’s

Place,” History of Mining in Arizona)

NEXT TIME: ALONG THE RUBY ROAD

The Ring Family Mystery

Back to List of Columns